When considering short-term applications, the NanoStoma could be readily employed to restart research activities involving reverse vesicles—which have not seen much progress. As a background, think of reverse vesicles as just normal vesicles but the inside and outside of the vesicle is entirely hydrophobic solvents, either oil or other organic solvents, while the membrane is composed of an amphiphilic lipid bilayer with the hydrophobic head facing inside. Seeing that research in this field—particularly in conjunction with DNA nanotechnology—is practically uncharted territory, exceptionally novel and interesting things could be developed. These novelties can range from simple modeling of the dynamics between hydrophobic molecules and proteins such as in the case of steroid hormones, to highly sophisticated systems of localized molecular programming.

In the long-term, the NanoStoma’s basic concept might be developed further and perfected into fully applicable gas delivery systems, whose functionalities would be even beyond what we could imagine DNA nanotechnology is even capable of. What we, Team Sendai, can think of is as follows.

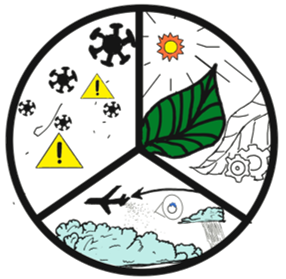

- Fully functioning artificial leaves, with complete synthetic metabolism systems that convert carbon dioxide into sugars, or other organic compounds, and oxygen. The NanoStoma acts as the gate to allow the artificial leaf cells to get access to gaseous carbon dioxide, the opening of which might be controlled by light to ensure maximum efficiency.

- Highly sensitive airborne pathogen detectors. The NanoStoma can act as a more developed version of the current one with an aptamer region that detects specific airborne pathogens based on their biomarker such as a virus’ spike protein. As such, this detection system can open the way for more efficient epidemiological policies.

- Gaseous environment modulators. The NanoStoma acts such that it detects the local gaseous environment it is exposed to and activates action circuits to modulate such environment. For example, it can help in highly detailed modulation of the microscale carbon dioxide conditions when growing synthetic tissue.

Reference

Barber, J., & Tran, P. D. (2013). From natural to artificial photosynthesis. Journal of The Royal Society Interface, 10(81), 20120984. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2012.0984

Malik, S. (2018). Cloud Seeding; Its Prospects and Concerns in the Modern World -A Review. International Journal of Pure & Applied Bioscience, 6(5), 791–796. https://doi.org/10.18782/2320-7051.6824

Michl, J. (2011). Towards an artificial leaf? Nature Chemistry, 3(4), 268–269. https://doi.org/10.1038/nchem.1021

Sivakumar, R., & Lee, N. Y. (2022). Recent advances in airborne pathogen detection using optical and electrochemical biosensors. Analytica Chimica Acta, 1234, 340297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2022.340297

Zhai, T., Wei, Y., Wang, L., Li, J., & Fan, C. (2023). Advancing pathogen detection for airborne diseases. Fundamental Research, 3(4), 520–524. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fmre.2022.10.011