OVERVIEW

The NanoStoma is a square plate DNA origami structure with a built-in slit in the middle of it that possesses a mechanism that allows it to open and close in response to light stimuli. The concept focuses on the controllable creation of a tunnel-like hydrophobic environment that allows movement of gas molecules. The structure would have the capability to be stacked and implemented in a soap bubble’s membrane, effectively connecting the two regions inside and outside of the bubble.

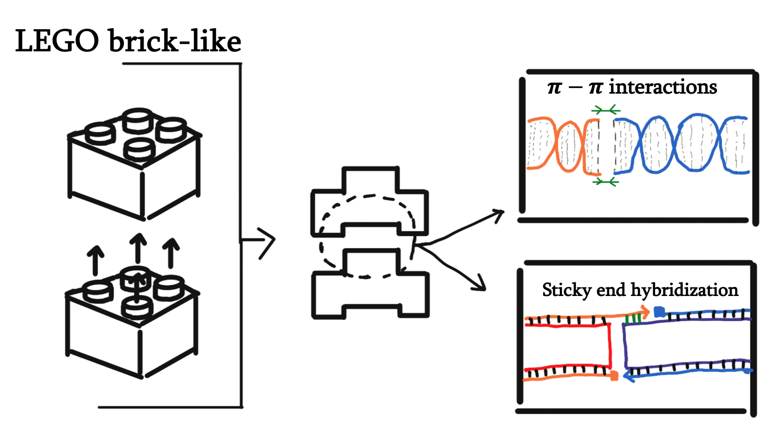

The light-inducible functionality of the structure comes from the use of azobenzene-modified DNA, which hybridizes or denatures depending on the 3D conformation of the inserted azobenzene, which can be changed through exposure of specific wavelengths of light. The light exposure would then trigger all the stacked monomers opening or closing, which effectively forms or abolishes the hydrophobic tunnel. The stacking mechanism is highly adaptable as it is based on both shape-shape complementarity through blunt-end stacking interactions and also sticky end hybridization, allowing tailorable size depending on the thickness of the soap membrane used. In addition, due to this mechanism, a standard curve of stacking effectiveness based on magnesium ions can be easily created and reproduced just based on observation of formed structures.

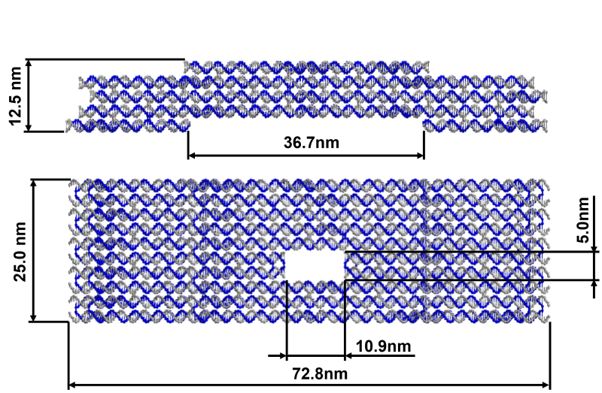

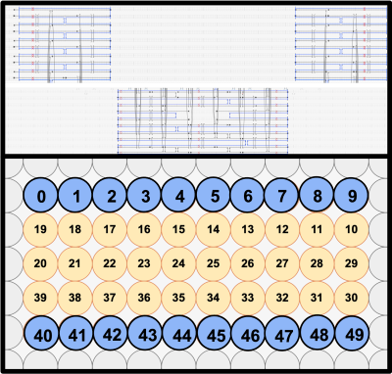

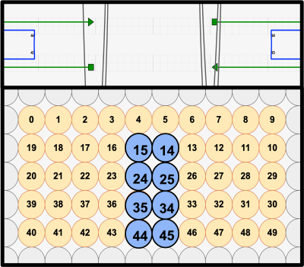

Our main structure comprises five layers of helix bundles, with the top and bottom ones being optimized for the stacking functionality. The cross-section of the main layers features a 10-helix bundle with the 4th and 5th helices acting to form the central slit. The origami uses the p8064 ssDNA as the scaffold and a total of 236 staple strands.

THE MAIN STRUCTURE

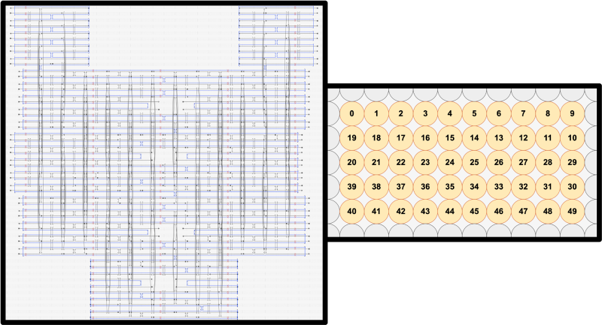

The main structure was designed using caDNAno. caDNAno is a software that specifically is aimed to be used to design DNA origami through a simplified interface that optimizes DNA origami design through ‘mapping’ of the single stranded scaffold strand and staple strands, along with their respective crossovers.

The layers were made from a single DNA Origami with crossovers that were designed to fold the long single sheet into five distinct layers. The lattice type was set to the square lattice due to the need of precise folding of the layers to realize a continuous slit and proper shape complementarity to allow self-stacking.

Single-stranded circular M13 bacteriophage DNA, p8064, (8064nt) were used for the scaffold, while 20-53nt-long strands (average of 34nt) were used for the staples, which amount to a total of 236 strands.

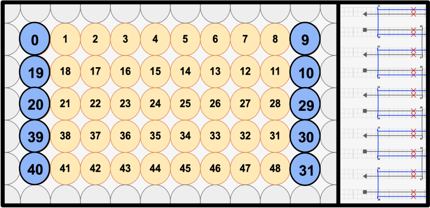

In order to prevent unwanted lateral stacking/aggregation, all most-lateral helices that are not involved in the vertical stacking mechanism were modified to include 3nt-long thymine overhangs. In addition, to prevent excessive torque and twisting of the structure, we included base skips every 48 bases (shown by red X marks), which match the realistic correction needed that accounts for the 10.5 bases/helix turn of DNA.

After designing, we checked the stability of our structure using the finite element analysis tool, CanDo.

In addition, we also made use of the coarse-grained molecular dynamics software, oxDNA, to simulate the movement and vibrations of the DNA strands in our structure to see if they would indeed form the intended structure in a realistic water-based environment.

THE SELF-STACKING BODY

In order to facilitate self-stacking, we decided to make use of shape complementarity. More specifically, we implemented both pi-pi interactions and sticky end hybridization.

In caDNAno, we designed the top-most and bottom-most layer to have complementarity in twenty different spots (two 10-helix-wide regions). Based on the calculations provided by a previous paper, the twenty different stacking positions should give stabilization energy to the stacked region to a degree of at least 232 kcal/mol. We also predict that the resulting stabilization energy has more effect in stabilizing the structure when compared to making changes to the structure or mechanism in order to minimize entropy.

THE SLIT

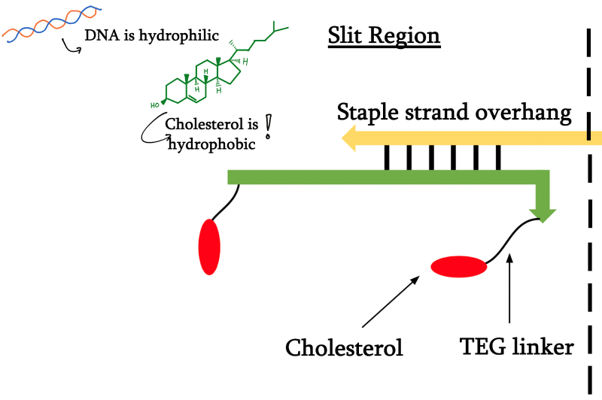

To facilitate the main function of the NanoStoma, a central slit that opens a way between both ends of each monomer is needed. We ended up designing the central slit to have a width of around 10.9nm in its original state. The positioning of this opening was carefully made on each layer to perfectly line up when the layers finally stack together, creating what is essentially a four-helix-long tunnel.

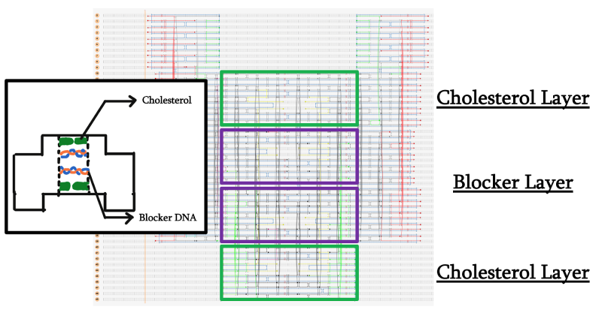

The slit spans four out of the five layers, the two inner ones being intended for blocker DNA and the outer ones for cholesterol integration. In order to facilitate these functional modifications, we added staple overhangs with specific sequences.

DNA modified with a cholesteryl-TEG moiety on both 5’ and 3’ ends was designed to specifically anneal to the appropriate layers’ staple overhangs.

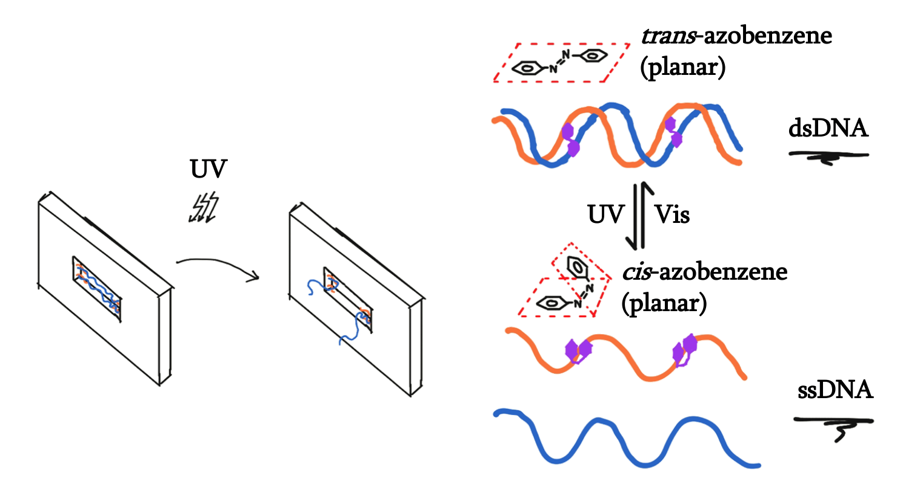

For our final idea, we want the formation of the hydrophobic tunnel to be inducible by light. In this attempt, we have decided to use azobenzene-modified DNA. Azobenzene itself switches its conformation from the planar trans form to the non planar cis form when exposed to ultraviolet light. When integrated into DNA, the non-planar form prevents that local region of DNA to bind to another strand, denaturing the double helix.

As such, we want to design the locking mechanism where the binding of the two middle strands connect the two staple overhangs. Within the hybridization region of the two strands, azobenzene moieties were to be integrated, therefore controlling the binding of these two strands, which therefore controls the opening and closing of the tunnel.

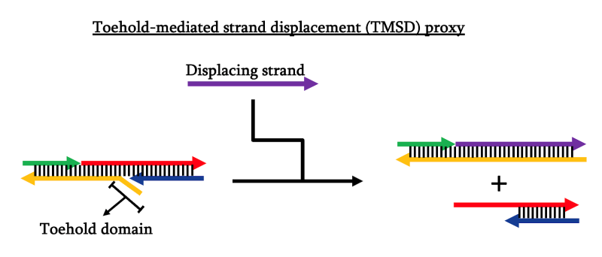

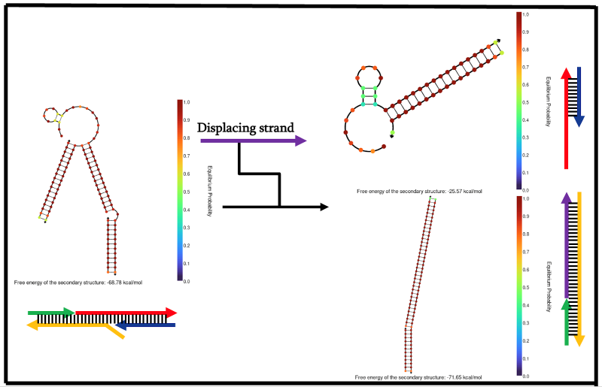

Before moving on to actual synthesis of the azobenzene-modified strands, we would like to test the locking mechanism on itself first to see whether the appropriate binding is energetically favored, i.e. actually formed. In this pursuit, we decided to use toehold-mediated strand displacement (TMSD) to act as a proxy of our azobenzene light inducibility. In this proxy, the stimulus of opening is the introduction of another strand that hybridizes completely with the toehold-possessing strand, therefore being more energetically favored and causing the whole structure to dissociate into two parts.

In order to maximize the chances of proper formation, we designed and tested our locking mechanism design using NUPACK. The NUPACK results came back positive with good equilibrium probabilities that our intended structures are formed and in a stable state.

REFERENCE

Douglas SM, Marblestone AH, Teerapittayanon S, Vazquez A, Church GM, et al. Rapid prototyping of 3D DNA-origami shapes with caDNAno. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009

Douglas, S. et al. (2009) “Self-assembly of DNA into nanoscale three-dimensional shapes”. Nature, 459(7245): 414-418

H. Dietz, S. M. Douglas, W. M. Shih, Folding DNA into twisted and curved nanoscale shapes. Science325, 725 (2009).

Hernández-Ainsa, S., Bell, N. A. W., Thacker, V. V., Göpfrich, K., Misiunas, K., Fuentes-Perez, M. E., Moreno-Herrero, F., & Keyser, U. F. (2013). DNA Origami Nanopores for Controlling DNA Translocation. ACS Nano, 7(7), 6024–6030. https://doi.org/10.1021/nn401759r

J. N. Zadeh, C. D. Steenberg, J. S. Bois, B. R. Wolfe, M. B. Pierce, A. R. Khan, R. M. Dirks, N. A. Pierce. NUPACK: analysis and design of nucleic acid systems. J Comput Chem, 32:170–173, 2011.

Karabıyık, H., Sevinçek, R.,& Karabıyık, H. (2014). π-Cooperativity effect on the base stacking interactions in DNA: is there a novel stabilization factor coupled with base pairing H-bonds? Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, 16(29), 15527. https://doi.org/10.1039/c4cp00997e

Mariurt, J. and Doty, P. (1961) “Thermal Renaturation of Deoxyribonucleic Acids”. Journal of Molecular Biology, 3: 585-594

Lee, H., Dehez, F., Chipot, C., Lim, H.-K.,& Kim, H. (2019). Enthalpy–Entropy Interplay in π-Stacking Interaction of Benzene Dimer in Water. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation, 15(3), 1538–1545. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jctc.8b00880

P. W. K. Rothemund, Folding DNA to create nanoscale shapes and patterns. Nature 440, 297 (2006).

Yoo, J.,& Aksimentiev, A. (2015). Molecular Dynamics of Membrane-Spanning DNA Channels: Conductance Mechanism, Electro-Osmotic Transport, and Mechanical Gating. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters, 6(23), 4680–4687. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b01964