BACKGROUND

For a long time, building nanostructures have been dominated by the use of inorganic materials such as polymers and metals. However, the advent of DNA nanotechnology has launched a myriad of opportunities to build nanostructures using biomolecules, with the inherent advantage of being easier to engineer for direct biological relevance. For example, DNA origami exploits the nature of Watson-Crick base pairing to allow creation of extremely small structures out of DNA with sub-nanometer precision. The energetically more stable form of the “folded” form prompts the DNA to self-assemble without needing any additional process. The basic structure of a DNA origami consists of one strand of ssDNA called the “scaffold”, which then pairs with the designed shorter strands called the “staple” strands to realize the intended folding.

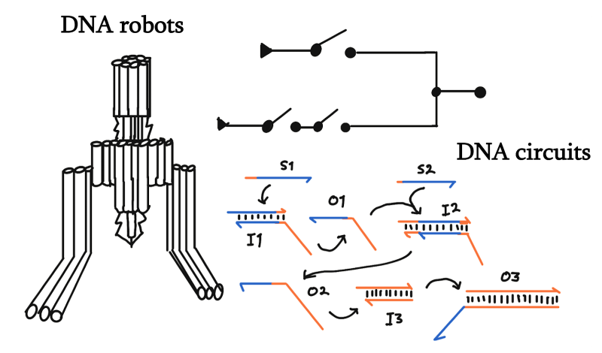

Several different innovative structures and functionalities have been made using DNA. These include fully functional DNA robots with specific functionalities, complex DNA logical circuits that mimic the functionality of electronic circuits, and even a nanometer-sized replica of the Mona Lisa!

Other structures come in the form of nanopores. As the name suggests, they are incredibly tiny channels or openings on the nanoscale, typically measuring just a few nanometers in diameter. They play a pivotal role in various scientific applications, particularly in the fields of biotechnology and materials science. Nanopores can be found in natural systems, such as cell membranes, where they facilitate the transport of ions and molecules. In other words, DNA membrane channels are being engineered to mimic a natural system of chemical exchange: where molecules pass between two distinct environments. In nature, chemical exchange systems govern various phenomena that keep all organisms alive and even keep the planet together.

THE PROBLEM

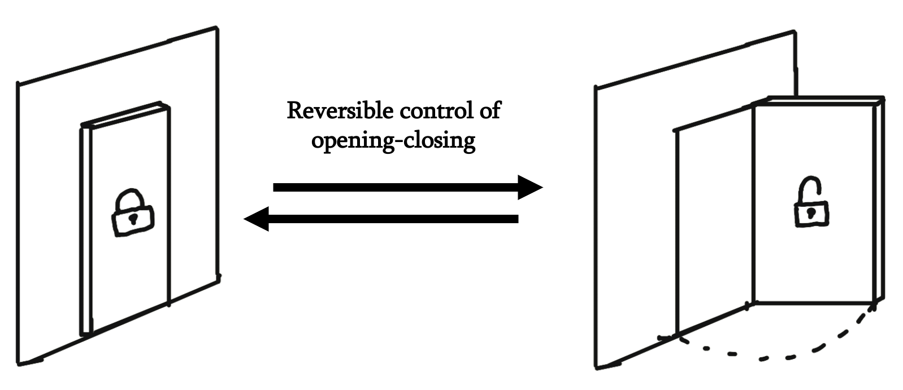

Despite that, most DNA channels struggle to really mimic the functionality of naturally occurring ones. For example, the reversibility of the opening and closing of a natural membrane channel plays a crucial role in how it establishes its importance. Many opening-closing mechanisms devised in DNA origami require the removal of an existing component of the system, as is usually done through strand displacement reactions or enzymatic digestion of DNA strands. As such, restoration to the initial state without ‘refueling’ is usually difficult, unrealistic, or just plainly impossible.

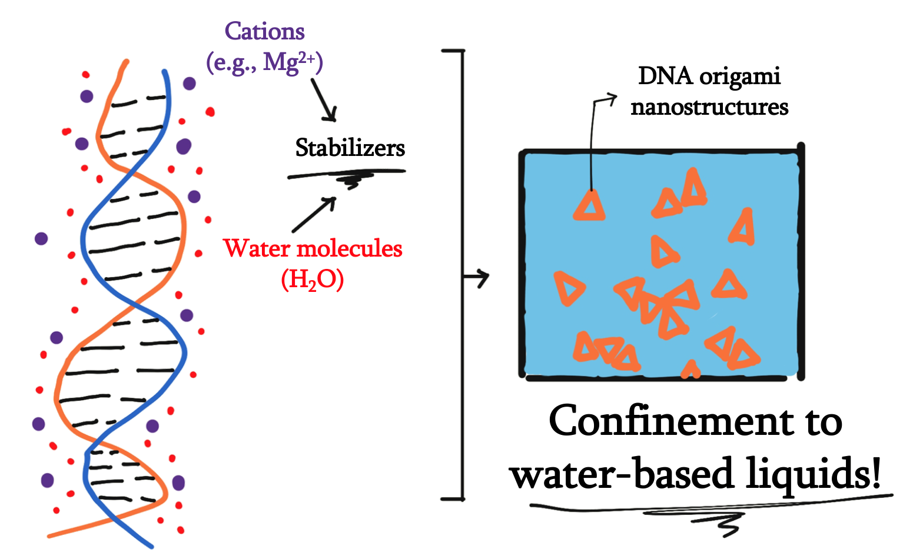

In addition, the operation of DNA nanopores is currently tied to liquid environments. Of the many chemical processes in nature, many of them require the interaction between solution and gas, or even occur solely in the gaseous phase. Therefore, to truly mimic functionality of these systems, there needs to be a novelty in enabling DNA origami nanostructures to interface environments that are in different states of matter. As such, the liquid-centric nature of current DNA nanopores leaves the full potential of DNA nanostructures’ functionality practically unexplored.

To summarize, inability to interact with dry environments, coupled with the inability to reversibly open and close without additional input of DNA or protein (which would also be impossible in dry environments) presents a unique and crucial challenge for the whole field of biomolecular nanotechnology. This liquid-centric trait prevents more complex molecular robots in reaching its full potential not only in technical functionality but also in real-world applications. For example, the inability to function in environments surrounded by air severely limits its applicability in dry environments, where humans live and many causes of our current problems lie, such as climate change and airborne pathogens.

With the elaboration above, we came up with several questions:

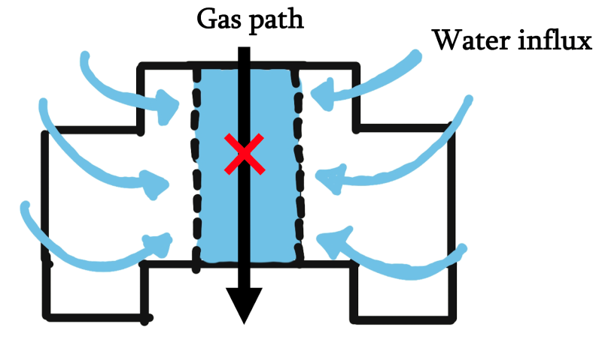

What if we can create a tunnel-like structure with DNA that allows gaseous molecules to pass through?

However, in order to do that, then we must also wonder what if we devised a way for a DNA nanostructure to connect two ‘dry’ environments while still facilitating the ionic conductivity required for successful assembly of it?

Would that set a foot towards application of DNA origami devices to be able to transmit gaseous molecules between different compartments of nanorobots, thus allowing gaseous sensing?

Would it be able to propel research and technology in fields requiring very precise chemical control, such as materials engineering and finemechanics?

Furthermore, in this unique environment, what if we devised a novel mechanism for reversible opening-closing of the DNA channel?

Would it be possible then in the future to use such technology to create complex systems that rely on gas exchange to create devices that control greenhouse gas emissions? Maybe fully photosynthesizing artificial leaves? Or even fine-tune weather control? All through the use of DNA-based nanostructures. (See more in-depth elaboration on our Future page!)

THE CHALLENGES

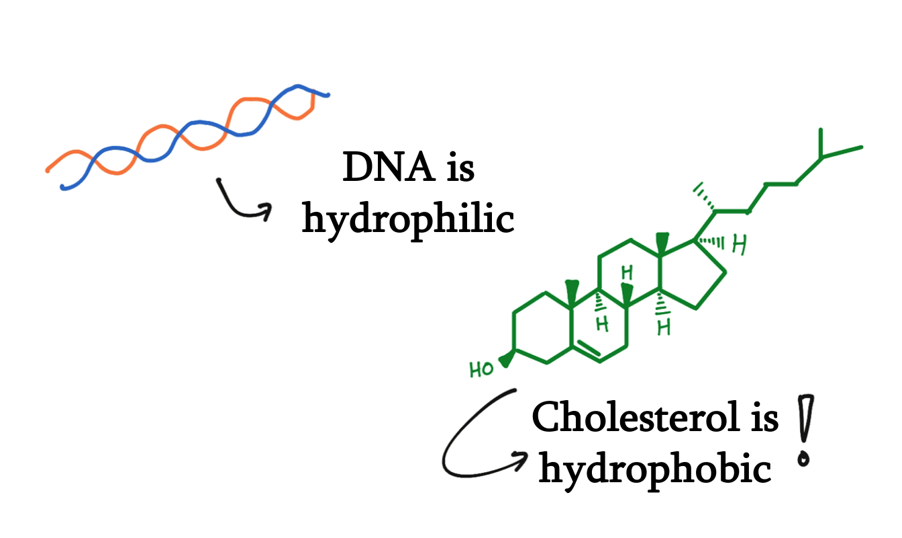

In considering our question, we come across the first challenge: the hydrophobic environment required to facilitate the movement of gas. This challenge is outlined by the inherent hydrophilicity of DNA, which would also mean that design of DNA origami and ideal working conditions would be those where it can be stabilized by water molecules.

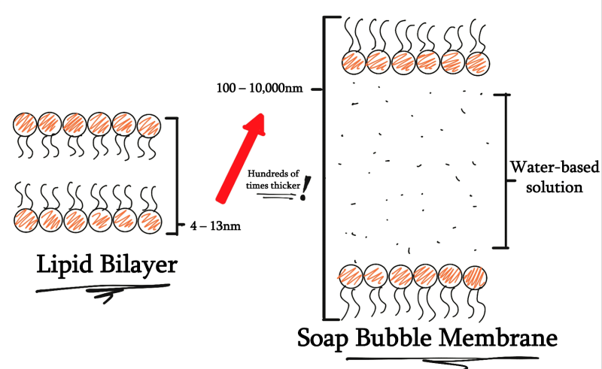

In order to transport gas between two distinct places, those two places would naturally be filled with gas and the transporter structure would need to be placed in between these gas chambers. However, current DNA nanostructures that transport molecules are usually embedded in a lipid bilayer membrane, which would mean that they connect between two hydrophilic environments: a no-go for gas exchange.

Our next concern comes when we consider the structure to operate in a soap bubble’s membrane, since it is probably the simplest naturally occurring structure that bridges two different regions of gas using a water-based liquid. The membrane of a soap bubble is variable in thickness, and the thickness is several orders larger than what can possibly be made from a single DNA origami.

Due to there is virtually no research done in this field, there is a very limited amount of established research methods that validly test mechanisms of gas transport using biomolecular nanotechnology.

OUR SOLUTION

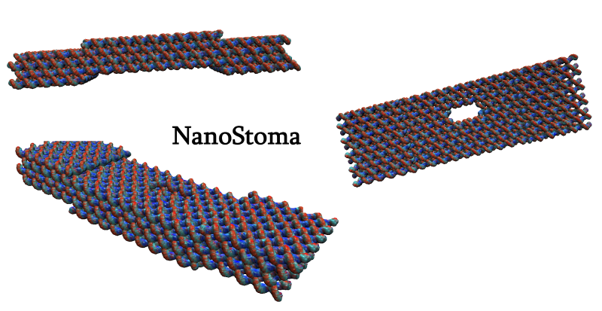

We devised a DNA origami valve, called the NanoStoma, designed to self-integrate into a soap bubble’s membrane and facilitate light-inducible gas exchange.

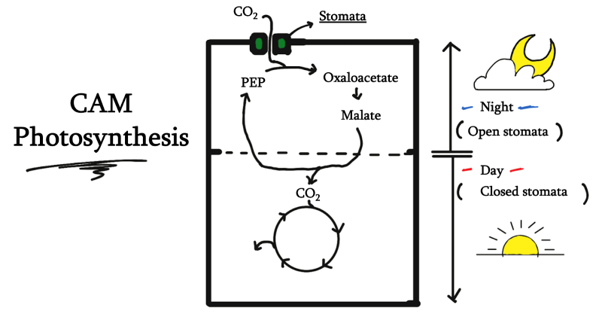

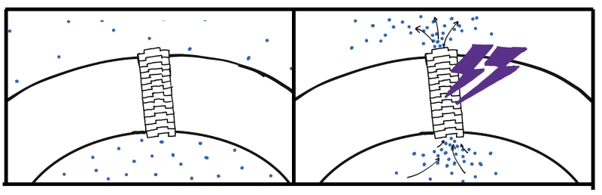

Our DNA Origami structure was designed to mimic the structure of stomata found on plant leaves, which open and close to control gas exchange for photosynthesis. More specifically, we were inspired by the stomatal opening system of CAM plants, which entails stomatal opening during nighttime and closing during daytime, controlled by blue light exposure. The NanoStoma self-stacks and integrates itself to the membrane of a bubble, connecting the air space inside and outside of the bubble. In its initial state, blocker DNA strands block the resulting tunnel, preventing gas molecules from traveling between the chambers. When exposed to UV light, the photoresponsive groups within the DNA dissociate the blocker DNA duplex, opening the tunnel and allowing the passage of molecules. The mechanism by which the NanoStoma operates is detailed in the Design section.

The NanoStoma self-stacks and integrates itself to the membrane of a bubble, connecting the air space inside and outside of the bubble. In its initial state, blocker DNA strands block the resulting tunnel, preventing gas molecules from traveling between the chambers. When exposed to UV light, the photoresponsive groups within the DNA dissociate the blocker DNA duplex, opening the tunnel and allowing the passage of molecules. The mechanism by which the NanoStoma operates is detailed in the Design section. To overcome the hydrophilicity problem, we made use of cholesterol, which is widely used in DNA nanotechnology research.

Our structure provides a fairly simple yet elegant solution to the problem of interest. Being designed purely out of DNA origami, it provides an easy-to-understand proof of concept that in the future allows for high potential of further optimization and modification by merging it with technologies such as synthetic proteins and adsorption onto inorganic nanoparticles. We also characterized and proposed novel use of the unique environment found in the membranes of soap bubbles and reverse vesicles, which have seen limited use in the field of biomolecular nanotechnology.

GOALS

As is the case with other novel things, there are a lot of things that need to be proven to establish the novelty completely. In our project, as far as we know, we are the first group of people to even attempt to create a DNA nanodevice that interacts with gas and hydrophobic environments. As such, there needs to be a lot of rigorous scientific proof to really be able to justify this as a fully functioning novel structure, proofs that would need a considerable amount of funding and cutting-edge research facilities that are reserved for highly ambitious research groups.

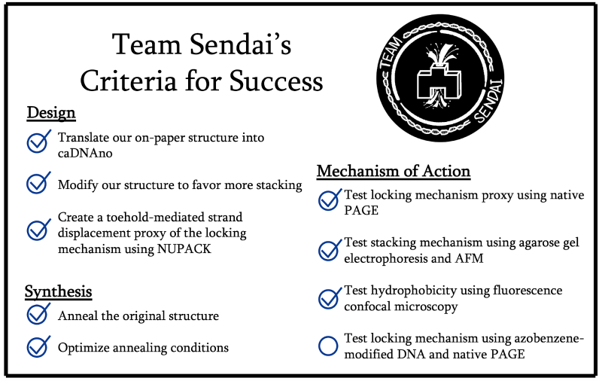

BIOMOD, on the other hand, gives relatively a very short amount of time when compared to a traditional research project on subjects such as these. As such, we have focused our attempts at providing the foundational truth of our idea and have listed the points below as our criterias for success in BIOMOD 2023.

FEASIBILITY

Regarding the feasibility of our project, the main hindrances come in the form of time and cost. We have designed the structure to be as simple as possible to provide the foundational proof of our concept. However, even with such simplicity, a considerable amount of funding and time—mainly in tweaking and optimizing design choices—is still needed. In addition, the novel ideas and concepts in our project have been practically unexplored in the literature, needing even more time to explore and empirically establish what is possible and what is not.

As such, as with our criterias for success, we have focused to maximize the feasibility of our project by aiming to gather empirical evidence regarding each functional part in the system of our nanodevice, providing a clear proof of the mechanisms and allowing future projects to focus on combining such mechanisms into a fully applicable system.

In ensuring high productivity, the project was performed with limited strictness regarding each person’s role, allowing both focused work in each of the assigned roles but also the ability to sub-in in case of the unavailability of people or the sheer amount of work needed to be done in a given day, which sped up the project and made sure that each member is fully aware of the project’s progress. We also planned regular frequent meetings with our mentors to let them know of our progress and to gather advice, not only on scientific truth but also feasibility (DNA order times, availability of equipment, etc.).

For details on our construct, the implementation of the final structure may come with difficulties at first.

Concerns might arise regarding the light-controllability of the structure, especially regarding its specificity. In addition, since the structure is modular and self-stacks, concerns might arise regarding whether all monomers will truly properly function and open the tunnel when exposed to the light stimulus. In this case, we want to highlight the specificity of azobenzene—the photoresponsive molecule we used—as it has been used in other applications. Because the photoresponsivity comes from the single molecular structure of azobenzene, it is highly preserved unless that structure is broken i.e. covalent bonds were broken, which would need a considerable amount of energy. In addition, studies have shown that chemical modifications to the azobenzene group allow for changes and fine-tuning of the wavelength that the azobenzene-derived moiety responds to, adding to the adaptability and tunability of the locking specificity.

Other concerns may come in the form of even if the locking mechanism works perfectly, the size of gas molecules would simply be too small to get blocked by the blocker DNA. However, we would like to highlight that the structure stacks and creates a homogeneous polymer with hundreds of monomer, each one having blocker strands in positions that would be slightly different from each other due to natural molecular motions, which effectively drives the probability distribution of successful blockage of gas molecules to the highly effective region. In addition, with more and more technological advances being developed to directly modify the DNA molecule, modifications can be added to increase the effective molecule size or perform electrostatic repulsion of specific gas molecules, adding to the efficiency of the blocking.

REFERENCE

Asanuma, H., Liang, X., Nishioka, H., Matsunaga, D., Liu, M., & Komiyama, M. (2007). Synthesis of azobenzene-tethered DNA for reversible photo-regulation of DNA functions: hybridization and transcription. Nature Protocols, 2(1), 203–212. https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2006.465

Asanuma, H., Liang, X., Yoshida, T., & Komiyama, M. (2001). Photocontrol of DNA Duplex Formation by Using Azobenzene-Bearing Oligonucleotides. ChemBioChem, 2(1), 39–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/1439-7633(20010105)2:1<39::AID-CBIC39>3.0.CO;2-E

Douglas, S. et al. (2009) “Self-assembly of DNA into nanoscale three-dimensional shapes”. Nature, 459(7245): 414-418

Duckett, D., Murchie, A. and Lilley, D. (1990) “The role of metal ions in the conformation of the four-way DNA junction”. The EMBO Journal, 9(2): 583-590

COCKBURN, W. (1983). Stomatal mechanism as the basis of the evolution of CAM and C 4 photosynthesis. Plant, Cell & Environment, 6(4), 275–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-3040.ep11611925

Gao, M., Kwaria, D., Norikane, Y., & Yue, Y. (2023). Visible‐light‐switchable azobenzenes: Molecular design, supramolecular systems, and applications. Natural Sciences, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.1002/ntls.20220020

Hernández-Ainsa, S., Bell, N. A. W., Thacker, V. V., Göpfrich, K., Misiunas, K., Fuentes-Perez, M. E., Moreno-Herrero, F., & Keyser, U. F. (2013). DNA Origami Nanopores for Controlling DNA Translocation. ACS Nano, 7(7), 6024–6030. https://doi.org/10.1021/nn401759r

Ohmann, A., Göpfrich, K., Joshi, H., Thompson, R. F., Sobota, D., Ranson, N. A., Aksimentiev, A., & Keyser, U. F. (2019). Controlling aggregation of cholesterol-modified DNA nanostructures. Nucleic Acids Research, 47(21), 11441–11451. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkz914

P. W. K. Rothemund, Folding DNA to create nanoscale shapes and patterns. Nature 440, 297 (2006).

Qian, L., & Winfree, E. (2011). Scaling Up Digital Circuit Computation with DNA Strand Displacement Cascades. Science, 332(6034), 1196–1201. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1200520

Thubagere, A. J., Li, W., Johnson, R. F., Chen, Z., Doroudi, S., Lee, Y. L., Izatt, G., Wittman, S., Srinivas, N., Woods, D., Winfree, E., & Qian, L. (2017). A cargo-sorting DNA robot. Science, 357(6356). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aan6558

Tikhomirov, G., Petersen, P., & Qian, L. (2017). Fractal assembly of micrometre-scale DNA origami arrays with arbitrary patterns. Nature, 552(7683), 67–71. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature24655